Written by: Johnny Wood

What happened to the birds, fish and marine wildlife that used to thrive in the wetland banks of Florida’s Kissimmee River?

Against all odds… they are returning.

Much of the Kissimmee’s original course and ecosystem have now been restored following a $1 billion restoration project that has been more than 20 years in the making. A rescue project has reversed decades of biodiversity decline caused by building canals and waterways to control flooding and hurricanes.

Engineering an ecosystem collapse

The river meanders its way from the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes in northern Florida, winding more than 100 miles through lush wetlands to Lake Okeechobee further south, where its waters feed into the Everglades ecosystem. At least, it used to.

Back in the 1960s, in an engineering effort to control the threat of severe storms and flooding, the US Army Corp of Engineers clipped the meandering river’s curves, turning it into a 30-foot deep, 300-foot wide, 56-mile long, straight-line drainage canal. The deep-water channel swiftly moved river water through the wetlands to Lake Okeechobee, then through newly-built canals out to the ocean.

While the short-term impact prevented some flooding, the fast flowing water robbed fish populations of oxygen and left pollutants in the water, instead of the wetlands absorbing them, according to South Florida Water Management District.

The damage to river ecosystems devastated surrounding wildlife and their habitats, decreasing waterfowl numbers by around 90 percent of previous levels, while the area’s bald eagle population fell by more than two-thirds. Some other bird, fish and mammal species disappeared from the river’s ecosystem.

Restored wetland habitats

Fast-forward to today and the Kissimmee wetlands are once again rich with marine life, birds and mammals.

The transformation is the result of a collaborative effort by the US Army Corp, state, federal and local partners to repair the environmental damage. Forty miles of wetlands – almost half of the river’s length – have been regenerated by filling in more than 20 miles of the channel with sediment, and excavating the river’s natural bends to reestablish its old course.

The results speak for themselves. As oxygen returns to the waters, fish, insect and bird populations are increasing and some of the species that disappeared have returned, such as ibis and sandpipers.

Data shows that the restoration meets or exceeds the expectations set at the beginning of the project, according to the Center For Environmental Studies, Charles E Schmidt College of Science in Florida.

A similar success story can be found in Chicago where, 50 years after the city’s Clean Water Act, the river is said to be thriving – most recently proved by the appearance of a giant snapping turtle in its waters.

Kissimmee river: A blueprint for tackling biodiversity loss

The scale of biodiversity loss and environmental damage to the planet has not gone unnoticed.

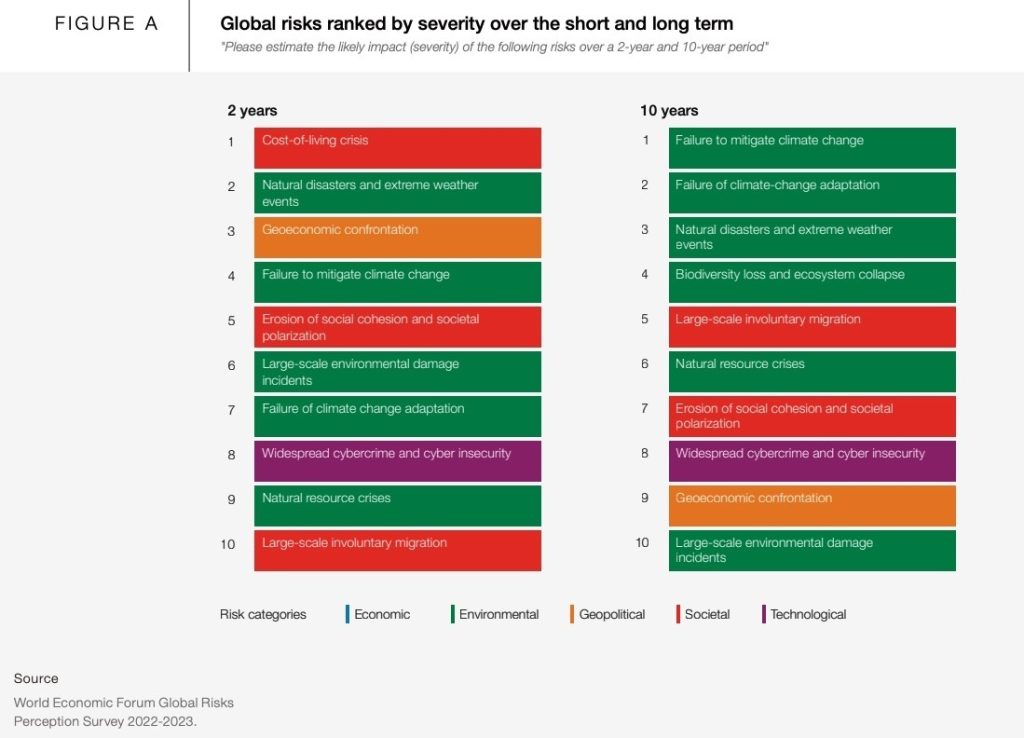

Large-scale environmental damage ranks sixth on the top 10 list of threats faced by humanity in the coming two years, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2023.

Looking further ahead, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse is seen as the fourth-largest threat to humans in the next decade, while incidents of large-scale environmental damage – similar to what happened to the Kissimmee River – also feature in the top 10.

As the largest river restoration project in the world, reviving the Kissimmee River and its wetlands ecosystem could provide a blueprint to reverse other environmental damage to rivers and waterways.

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum