Written by: Rabul Sawal

In June, Dormaida Sihotang and dozens of other women from Dairi district in Indonesia’s North Sumatra province arrived in Jakarta to plead with authorities to stop a zinc mine, two decades in the making, that could one day wipe them out.

“We came here to get across that our sources of water and our lives in Dairi will be threatened,” Dormaida said in late June outside Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

A month later, a court in Jakarta sided with Dormaida and the Dairi women, instructing the ministry on July 24 to revoke the environmental permit authorized to PT Dairi Prima Mineral (DPM) in August last year.

DPM is a mining company based in Dairi’s Sopokomil village, near the caldera of Lake Toba. The company is majority-owned by China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Co. Ltd., with Indonesia’s Bumi Resources owning the remaining 49 percent.

In 1998 Indonesia’s central government granted DPM a contract of work to mine beneath the highland ridges in the Barisan mountain range. The proposed work area is now almost 25,000 hectares (62,000 acres), straddling North Sumatra and Aceh provinces.

Underground surveys indicate a vast store of galena, a key ore of lead and silver, and zinc sulfide, the main zinc ore. Some estimate the vault contains around 5 percent of the world’s zinc, which is heavily relied on by the construction, automotive, electronics and other industries.

The Dairi farmers, supported by several Indonesian civil society organizations, have raised objections to the proposed mining development since the 2000s, citing threats to the community’s livelihoods, and risks of a humanitarian disaster from the mine’s waste storage.

Statistics agency data for 2021 show that agriculture — from community rice fields to fruit trees like durian — accounted for 42.9 percent of the region’s income in 2021. Farmers in Dairi say the mine threatens to eradicate swaths of that vital economic base.

“Dairi is fertile land. Just throw seeds and they’ll grow,” Dormaida said. “We have abundant sources of water and food, and lots of productive crops. So, please, do not mine here. What will we eat if all this is destroyed?”

Separately, international scrutiny of this risky project has long focused on the potential for structural failure of a dam constructed to store mining tailings, the toxic sludge left over after separating the target metal from its ore.

Up to five tailings dams experience catastrophic failure every year around the world. In January 2019, a dam holding back tailings at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine in Brazil’s Minas Girais state collapsed, sending an avalanche of mining waste downstream that wiped out a village. The disaster killed 270 people.

In the aftermath of the disaster, several large investors conducted risk assessments to uncover exposure to tailings dams around the world.

In 2022, the World Bank’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman published a review of the lender’s exposure to the Dairi mine via a $256 million equity investment in Postal Savings Bank of China (PSBC), which had provided capital loans to DPM.

The published review found PSBC no longer provided active financing to DPM, precluding a more detailed compliance investigation. However, the ombudsman’s preliminary review did find “shortcomings in the design of DPM’s tailings dam and assessment of associated risks compared with good international industry practice.”

Other engineers have raised urgent concerns about the plan, chiefly due to the potentially unstable foundation of volcanic ash compacted over millennia from the Toba volcano. The risk is compounded by the frequency of strong earthquakes in one of the world’s most seismically active zones.

“A structure built on a failing foundation will not stand,” engineer Richard Meehan wrote in a review of DPM’s tailings dam plans in 2019.

Court judgement

The July 24 judgement by the Jakarta court granted the Dairi plaintiffs’ lawsuit against the environment ministry “in its entirety,” according to a court transcript. The ruling requires the ministry to cancel the permit it gave to DPM in 2022.

“When the verdict came out we were elated, it revived the determination of the community,” said Monica Siregar, from the Diakonia Pelangi Kasih Foundation (YDPK), which has supported the Dairi farmers for years in their case against the mine.

The women who made the journey from Dairi to Jakarta ahead of the court case in June welcomed the ruling.

“I and others are happy that the court in Jakarta agrees that mining companies and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry have acted unfairly to us, as well as to the environment,” said Opung Rainim Purba, a woman farmer from Dairi.

Civil society groups are now expected to press the central government to follow through on the court’s judgement.

“[They are] determined to continue to be farmers, rather than fall for the company’s sweet talk about working in the mining area,” said Melky Nahar, who leads the Mining Advocacy Network (Jatam), a prominent civil society group.

However, the July 24 judgement may not be the final say on DPM’s plan to uncover up to 5 percent of the world’s reserves of zinc from a fragile environment. The environment ministry can appeal the decision at a higher court.

“We ask the respondents to respect the judges’ decision and carry out the court’s order to cancel the granting of an environmental feasibility permit to the mining company DPM,” said Tongam Panggabean, executive director of Legal Aid and Advocacy for the People of North Sumatra (Bakumsu), a civil society group that has led the community’s legal fight against the mine.

The women farmers of Dairi told Mongabay they would continue to fight against the zinc and lead mine.

“We are farmers, we eat from the farm, we live from farming,” Dormaida said at the demonstration in June. “From the land, not from lead.”

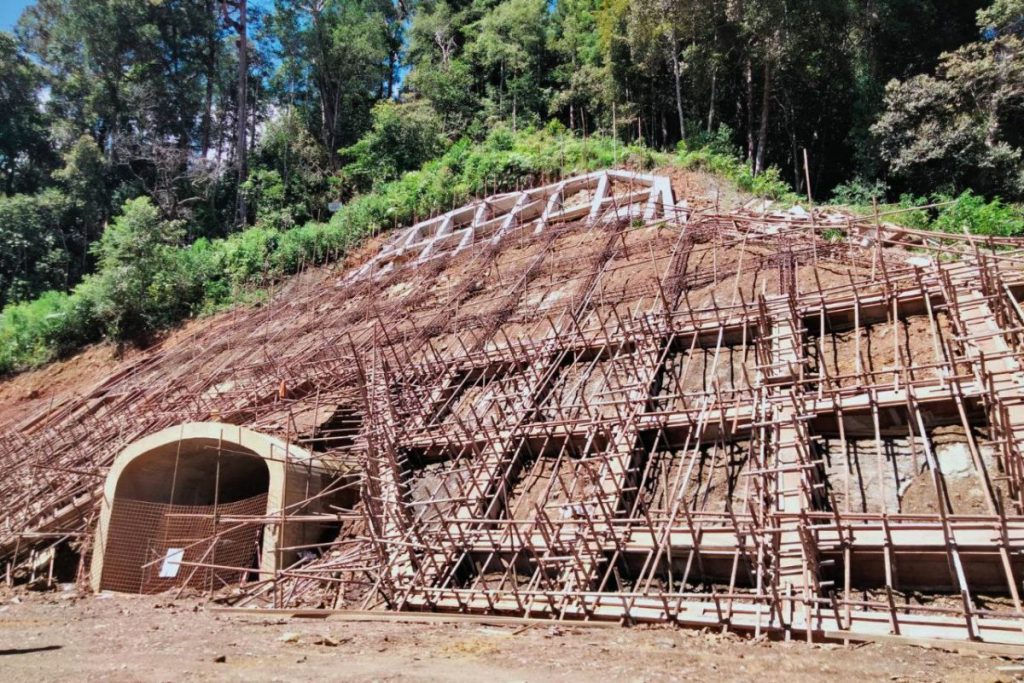

Header Image Caption & Credit: Dairi residents stood in solidarity with farmers and called for the rescue of Dairi from the zinc and lead mines. Image by Wednesday Sawal for Mongabay Indonesia.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay